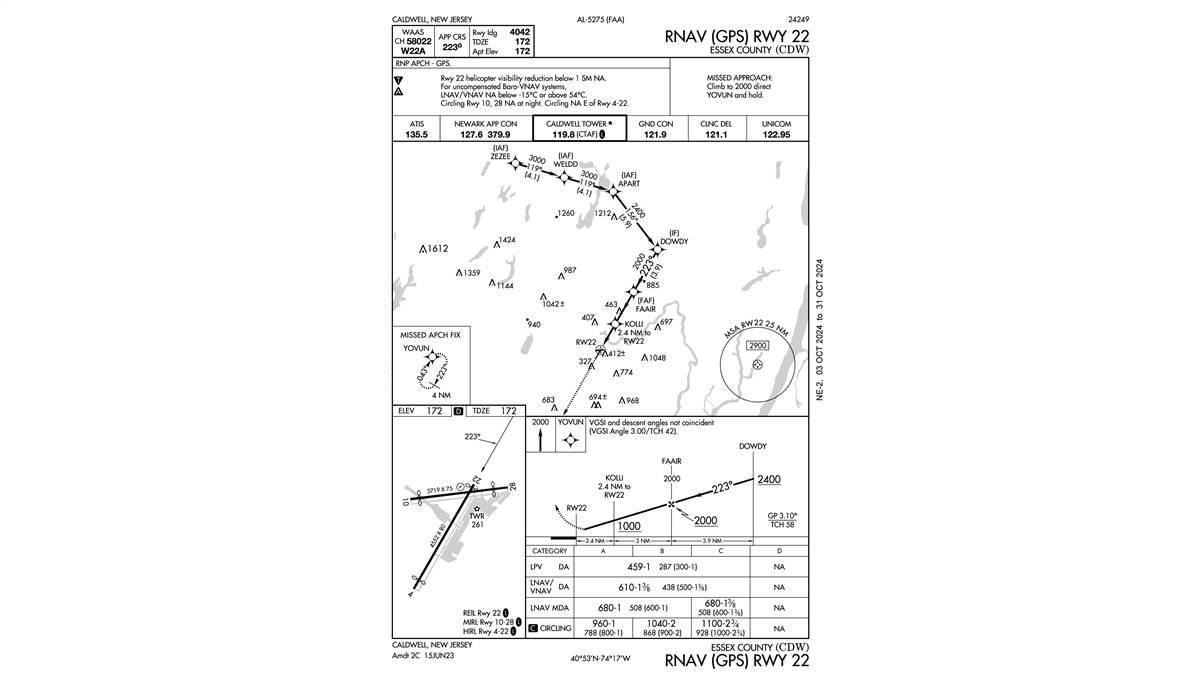

There are business jets as well as smaller general aviation airplanes here and quite a bit of flight school activity. It sits at the edge of the New York Class B airspace, which means it can be easy to operate into or out of the airport VFR with a minimum of communication with the overlying congested airspace, but to do so is to take certain risks. Having the helping hand of ATC is a smart move. However, if they’re too busy or you need to get in and out quickly and the weather conditions are suitable, VFR is an option.Glidepath control is critical, because the chart does not depict the roads that run just north of the field, which create thermal-like conditions.

CDW is only six miles to the north of Morristown Airport (MMU), which is another busy tower-controlled field. Just four miles to the north-northwest sits Lincoln Park (N07), which is just outside of the CDW Class D airspace. Overhead is airline traffic going to Newark, and bizjet traffic going to Teterboro. Runways 22 and 28 at CDW are right traffic. There’s a lot going on here and being part of the chaos means being on your toes.